“Are you okay?” Elysha asks as we sit down at the table to review the packet together.

“Yes,” I say, and I think I am. This isn’t sunshine and roses, but compared to the past, it shouldn’t feel so overwhelming.

In 1988, two days before Christmas, I survived a head-on collision with a Mercedes-Benz that sent me through a windshield headfirst. Paramedics performed CPR on me in the back of an ambulance to save my life.

Five years earlier, when I was 12 years old, I also required CPR from paramedics to save my life when I was stung by a bee, experienced an allergic reaction, and collapsed on my dining room floor.

I survived an arrest, jail, and a trial for a crime I did not commit.

I survived homelessness.

How could I not be okay today after surviving all of that? This should feel like nothing compared to all of that.

“Are you sure?” Elysha asks.

Yes,” I say, and think I mean it, but oddly, I’m not entirely sure. And it makes no sense.

Ever since Saturday, April 19, 1993, the answer to that question has always been, “Yes. Of course I’m okay.”

And it’s always been true. It’s always felt true.

I thought the answer would be an emphatic yes forever. Everything after April 19, 1993, has always seemed so easy to me by comparison. Problems that once loomed large have now become small. Challenges that once seemed insurmountable have become manageable.

Impossibilities suddenly became possible.

It might still be the case now. It should still be the case. I should be okay, but this somehow feels different, and I’m not sure why.

How could anything compare to the events on the night of April 19, 1993?

It’s just about midnight on a warm, spring night. The doors to the restaurant are locked. I’m managing a McDonald’s on Belmont Street in Brockton — one of the two jobs I’m working to save money for my legal fees.

My trial is still more than a month away.

My crew is cleaning up. Mopping, washing dishes, and scrubbing grills. I’m in the office at the back of the store, counting money at the safe. Ironically, I have another $7,000 in my hands — the same amount of money that went missing and got me arrested in the first place.

I’m stuffing the cash into another deposit bag when I hear the crash and know full well what is coming.

A police officer had visited the restaurant a week before to warn me about the three men who were robbing restaurants in the town, but I had known about the robberies long before the cop made his appearance. The McDonald’s on the other side of Brockton — where my girlfriend, Christine, was working — had already been robbed weeks before, and the Taco Bell that I could see outside my drive-thru window had been robbed less than a week ago.

In that robbery, an employee had been shot and killed.

So when I hear the crash of glass breaking, I know who is coming for me. Time seems to freeze for a moment. I look at the phone on the wall and then the bag of money in my hand. Back and forth.

Then I make the worst decision of my life.

I take that bag full of money — $7,000 in cash — reach into the back of the safe, and drop it down a chute that sends the deposit bag to a compartment at the bottom of the safe for which I do not have a key.

Why I do this, I’ll never know.

Seconds later, they are in the room with me. Three large men in black ski masks. They’ve already gathered my employees and shoved them into the office with me — two Haitian brothers who can’t speak English and a girl named Francis. She’s 18 years old and about to graduate from high school.

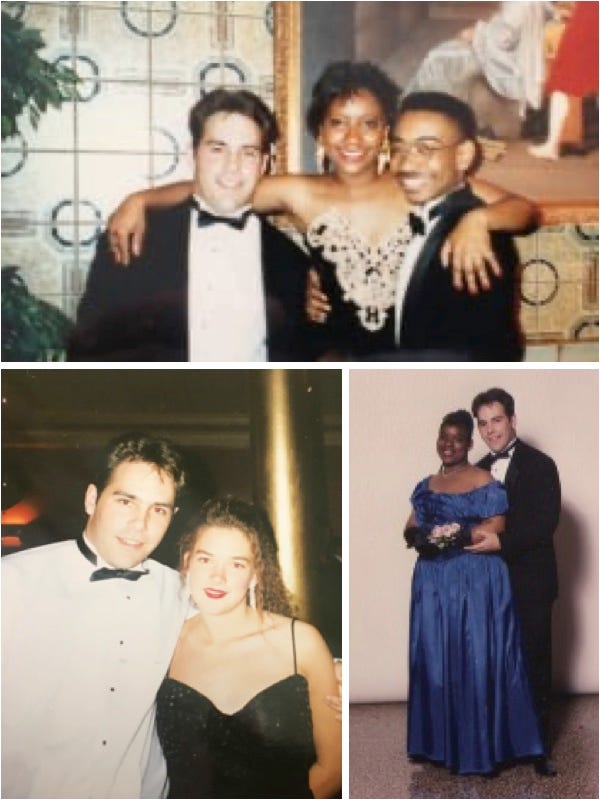

One month later, I’ll take her to her senior prom because her mother doesn’t trust her with anyone but me.

The three men order us to lie down on the floor, so we do, side by side. They tower over us. Three men in black shirts, black pants, and white sneakers, each holding a large, black gun. While two of them stand over us, a third begins to pull money from the open safe, emptying the drawers of their cash and cleaning out the petty cash box. It doesn’t take him long to realize that there isn’t enough money in the safe.

Something is wrong.

That’s when one of them grabs me. Picks me up by the collar and drags me over to the safe. He points at that bottom compartment of the safe and orders me to open it.

I tell him I can’t. I don’t have a key. I point to the placard that reads, “Manager does not have key,” but he doesn’t believe me or the placard.

“Open it!” he shouts, and when I tell him I can’t, he hits me on the back of my head with his gun. I instantly see stars. The world seems to flip on its head. Then he releases me. I drop to the floor, my face bouncing off the tile, then all three men begin kicking me in the ribs as hard as they can.

I curl into a ball, trying to protect my body, pleading with them to believe me. Between kicks, I try to rationalize with them. I’d open the compartment if I could. It’s not my money. I would give it all away if I could.

The irony of this moment is lost on me in my panic to protect myself from their attack:

I’m facing criminal charges for money that I did not steal, and now I’m being beaten for money that I’d be more than willing to give away.

Then they stop kicking. I try to turn myself over onto my side, but then I feel the cold metal of a gun pushed against the back of my head, pressing my face back down onto the tile. One of the men says, “I’m going to count back from three, and then I’m going to shoot you in the head if you don’t open that box!”

As he begins counting, I beg him to believe me. Between snot and sobs, I plead for my life.

“Three, two, one —”

Then there is a click.

It’s the loudest click in the history of the world.

I begin to cry. They laugh and begin to kick me again. They are kicking hard, but I can barely feel anything anymore. I try to crawl away because I can’t speak or breathe. I’m shaking and crying.

I’m falling apart.

Then one of them grabs me again. Pulls me back by my collar. I’m hit again with their gun. I see stars again, but this time, the blow somehow pulls me back into the world. I can think again. I start to plead my case again.

Then a gun is pressed against the back of my head, and once again, my face is pushed down onto the greasy tile floor. One of the men says, “This time there’s a bullet, and I’m going to shoot you if you don’t open that box.”

He doesn’t yell. He speaks calmly. Softly. He means it.

I know it. He is going to shoot me dead.

As he starts to count back from three again, something strange happens. Something I can never explain. All of the fear and anger that consumed me just seconds before is gone. It just falls away. Time slows down again. Maybe stops altogether. In that instant, all the pain, fear, and anger have given way to sadness and regret. I’m a 21-year-old kid, lying on the greasy tile floor of a fast food restaurant, and I’m about to die having done nothing with my life. I’m going to be murdered in this crummy, little office, and very quickly, in the blink of an eye, I will be forgotten by everyone forever.

Regret. In those fitful, final seconds, it consumes me. There is nothing else. It is overwhelming.

Then there is another click. Somehow louder than the last.

They laugh again.

I weep.

Then they are gone.

For the next 15 years, I suffer from undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder until I meet my Elyha. She tells me that I probably shouldn’t wake up every night screaming.

“Don’t worry,” I say. “It’s just my thing. Some people collect stamps. Some people play tennis. This is what I do.”

She says no. It’s not actually “a thing,” and after much debate, she sends me to a therapist.

After a long time, I get a little better.

The moment changes my life in countless ways, but most of all, it makes me relentless. It’s the moment upon which my life pivots. From that moment forward, I begin pursuing my dreams and my future with reckless abandon. The momentum that it brings to my life never subsides. From that moment on, I try like hell to fill every day with enough to make me feel satisfied.

Not a day goes by that I don’t find myself thinking about that moment on that greasy tile floor. Most days, I think about that moment more than you could imagine. In many ways, I’m still there, lying on that floor, gun to my head, trying to get up, trying to rid myself of the regret I felt about not having done enough.

Knowing what it’s like to stare at the final moments of your life, feeling like you haven’t done nearly enough, is both terrifying and inspiring.

It’s also made everything since that day seem small by comparison. Problems that rightfully consume the attention and time of others are tiny to me.

Few things ever bother me.

I stopped caring about things that others consider important.

In many ways, that moment was a gift — a terrible, horrific, violent gift that I would never wish upon anyone — yet I would never undo it, even if I could.

I didn’t think anything would ever frighten me as much ever again, and it might not, but this moment feels strangely, unexpectedly, inexplably close.

But why? My career and livelihood are in jeopardy, but not my life. As terrible and frightening and unsettling as this moment may be, the cowards who have done this aren’t threatening my life. No matter what happens, I’ll go on. I’ll continue to move forward.

I’ll have a future.

Then it hits me:

This one isn’t just about me. All of my other disasters have only involved me. No one else was ever at risk.

But Elysha has been threatened, too, as has my principal and friend.

Everything before this has rested squarely upon my shoulders. Struggle and strife have been my own.

Now, people I love are involved. And it feels like my fault. I still don’t believe I did anything wrong, but they are in trouble because I am in trouble.

They would both be perfectly fine without me.

This is different.

I don’t know if this feels worse, but it feels like a new kind of fear.

“Am I okay?” Elysha asked me.

What I should say is something like, “I don’t feel okay for the first time in a long time.”

Instead, I tell her I’m fine. When she looks doubtful, I add, “I promise.” It’s a lie, but I don’t want her to worry more than necessary, and I especially don’t want her worrying about me.

She has enough to worry about already. We both do.

Instead, I force a smile. “Let’s see what else they’ve written about me,” I say.

Elysha immediately turns to the page that angers her the most.

Is this not #18?

"Why I do this, I'll never know"

I think I know why you dropped the money down into the safe's locked compartment. I think it's becuase you were desperate for people to understand that you weren't a theif. You were about to stand trial for being a theif. I suspect your (explitive) stepfather accused you of being a thief. Your entire first novel was an exploration of what it means to be a thief.

I don't think it was planned or logical or even conscious. I'll bet in that moment of absolute terror, what bubbled to the top was maybe the most important existential need you had at the time - to be known as an honest man.

I'm so sorry that these awful things happened to you. I'm really glad that you lived through them so that you can contribute to the world.